JavaScript: async and await

async and await are new additions in the ECMAScript 2017 (ES8) specification as a syntactic sugar on top of JavaScript Promises. Their usage eases the way to write and read asynchronous functions besides making their syntax align more with traditional synchronous JavaScript functions.

The async keyword is placed before a function f to make it asynchronous, which then returns a promise.

async function f() {

//

}

We can also denote an async function with an ES6 arrow function notation as

const f = async () => {

//

}

We first consider a simple function pi() which returns the value of π. To wrap it along inside a Promise object, we insert the async keyword as follows:

const pi = async () => {

return Math.PI;

}

pi().then(res => console.log(res));

Now pi(), despite not being a Promise object initially, returned a Promise (after using async ) and the then() method is chained to it to get the resolved value.

JavaScript await

The await operator delays the async function until the Promise is resolved. Its use, however, is valid only inside the async function's body.

await can only be used inside an async function; outside of it, it will throw a SyntaxError.

Take a look at the async function below (it works without assigning async here), inside of which an instance of the Promise object is invoked without the await expression.

const pi = () => {

return new Promise((resolve,reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

resolve(Math.PI);

}, 1000);

});

}

const callPi = async () => {

pi().then(res => console.log(res));

console.log("PI");

}

callPi();

The console.log("PI") statement is after the pi().then() asynchronous call. But as the promise is timed to return after 1 second, console.log("PI") gets printed first, followed by the value of π after a second.

PI

3.141592653589793

We can do away with the callPi() function replacing it with a self-invoking function as follows:

const pi = () => {

return new Promise((resolve,reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

resolve(Math.PI);

}, 1000);

});

}

(async () => {

pi().then(res => console.log(res));

console.log("PI");

})();

Now if we assign await before the instance of the Promise, it delays the execution of the consecutive console.log("PI") statement till the Promise object is returned.

const pi = () => {

return new Promise((resolve,reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

resolve(Math.PI);

}, 1000);

});

}

(async () => {

await pi().then(res => console.log(res));

console.log("PI");

})();

The console.log("PI"); statement gets executed only after the Promise gets resolved/rejected.

3.141592653589793

PI

To handle rejected values in the returned Promise, you need to join the catch() method after then() as shown below.

(async () => {

await pi()

.then(res => console.log(res))

.catch(err => console.log(err));

console.log("PI");

})();

async/await with the fetch() Method

We construct another example with the fetch() method inside.

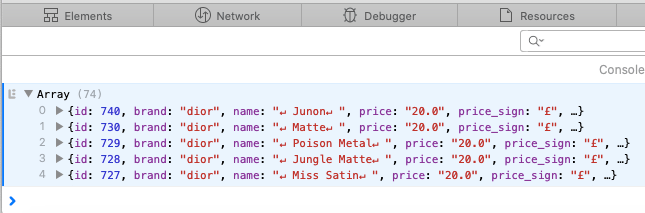

We will retrieve a list of makeup products of some beauty brand using Heroku's Makeup API, say, the brand Dior.

const makeup = async () => {

let response = await fetch('http://makeup-api.herokuapp.com/api/v1/products.json?brand=dior');

return await response.json();

}

makeup()

.then(data => console.log(data))

.catch(err => console.log(err.message));

The details of each item are printed into the browser's console.

Replacing Nested & Chained Promises w/ async &await

There often arise a case when the condition to make a subsequent promise call depends upon the result of the first request. For example, take the following scenario:

-

A biker logs in with his email and password into a garage website. A

fetch()call is initiated. -

A promise is returned, which contains his user id. This user id is used to fetch his other details to display in the dashboard, including his last servicing id. This is another

fetch()call after the first promise's return. -

Now the returned servicing id is passed into another

fetch()call to retrieve the servicing details.

Already you might have a scanty picture in your mind that this implemention requires nested asynchronous calls. This is one simple example where a subsequent asynchronous call depends upon the data of the preceding request. You cannot make the second call without the result of the first.

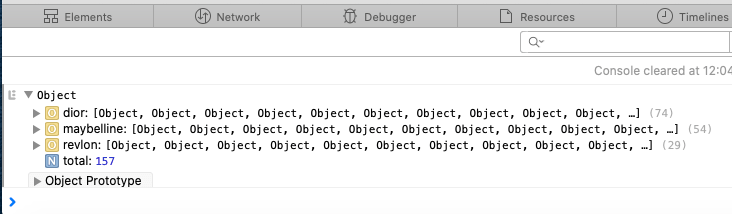

We will illustrate it with an example. Using Heroku's Makeup API, we will retrieve all the available makeup items from Dior, Maybelline and Revlon. Though (for the sake of simplicity) we do not involve any dependencies on the datas returned by promises here, the retrieval process goes like this: fetch Dior products first, then Maybelline, then Revlon.

After the last fetch() call, all the results returned by promises are resolved into a single JavaScript object.

const fetchDetails = (url) => {

return fetch(url).then(res => res.json());

}

const makeup = () => {

return new Promise(resolve => {

fetchDetails('http://makeup-api.herokuapp.com/api/v1/products.json?brand=dior').then((dior) => {

fetchDetails('http://makeup-api.herokuapp.com/api/v1/products.json?brand=maybelline').then((maybelline) => {

fetchDetails('http://makeup-api.herokuapp.com/api/v1/products.json?brand=revlon').then((revlon) => {

resolve({

'dior': dior,

'maybelline': maybelline,

'revlon': revlon,

'total': dior.length + maybelline.length + revlon.length

});

});

})

});

});

}

makeup().then(res => {

console.log(res);

});

Here is the output in the browser's console.

As long as we have only such few fetches, nested asynchronous calls look fine. But what if we have to fetch from over a 100 brands? The nesting would extend forever. This is when we enter the "Pyramid of Doom", also known as "Callback Hell". Forget the clutter, the code would be unmanageable!

This is where chaining promises comes in, offering a neater break from deep nesting. We attach the callbacks to the returned promises. The result is the same.

const fetchDetails = (url) => {

return fetch(url).then(res => res.json());

}

const makeup = () => {

let dior = maybelline = revlon = [];

return new Promise(resolve => {

fetchDetails('http://makeup-api.herokuapp.com/api/v1/products.json?brand=dior')

.then(res => dior = res)

.then(res => fetchDetails('http://makeup-api.herokuapp.com/api/v1/products.json?brand=maybelline'))

.then(res => maybelline = res)

.then(res => fetchDetails('http://makeup-api.herokuapp.com/api/v1/products.json?brand=revlon'))

.then(res => {

revlon = res;

resolve({

'dior': dior,

'maybelline': maybelline,

'revlon': revlon,

'total': dior.length + maybelline.length + revlon.length

});

});

});

}

makeup().then(res => {

console.log(res);

});

And better still, we can do away with the nestings and the chainings using async and await. Here is an example showing how they are implemented. The items of Dior are fetched first, then Maybelline's, then Revlon's.

const fetchDetails = (url) => {

return fetch(url).then(res => res.json());

}

const makeup = async () => {

const dior = await fetchDetails('http://makeup-api.herokuapp.com/api/v1/products.json?brand=dior');

const maybelline = await fetchDetails('http://makeup-api.herokuapp.com/api/v1/products.json?brand=maybelline');

const revlon = await fetchDetails('http://makeup-api.herokuapp.com/api/v1/products.json?brand=revlon');

return {

'dior': dior,

'maybelline': maybelline,

'revlon': revlon,

'total': dior.length + maybelline.length + revlon.length

};

}

makeup().then(res => {

console.log(res);

});